four thoughts on gail scott

1

Let us at last seek help in interpreting the dream of the 21st century. We must pay attention to juxtapositions. I pick up one of my favourite books, Gail Scott’s My Paris. In it, the narrator, named Gail, explores Paris as the millennium approaches against the backdrop of the Bosnian War. In her small “faux-deco” studio apartment she peruses a copy of The Arcades Project by cultural theorist and philosophical intimate Walter Benjamin. She names him “B.” To experience space through B’s lens, then, is to seek the dialectical image, a sort of placement of unlike objects (outdated commodities, usually, kitsch often) next to each other through which we suddenly see history for what it is: ongoing catastrophe. Gail visits the Musée Carnavalet:

It was about to rain. I saw the sky suddenly darkening through the open window. Further reflected in glass doors of Second Empire cabinets. Shelves flagging objects projecting images of bloody exuberance. Sèvres saucers with man waving Marie-Antoinette’s head. Man on plate gleefully collecting blood in basin. Gushing from guillotined neck. Citizen Le Sueur’s watercoloured cut-outs of citoyens and citoyennes: patriotic women’s club snug in bon-culottes: Marat on shoulders of supporters. Revolutionary army: sans culottes: apprentice butchers. Hunters. Citizens with placards: Vivre Libre Ou Mourir, Freedom or Death. Pasted in little groupings on deep blue sky. Hard flat edges. Precursing social realism. In succeeding rooms: succeeding revolutionary waves. Checked by defeat or Thermidor. When populace taking comfort in cosy interiors. Before hopeful ordinary people again building better barricades than ever. In defence of phantasmagoria of bourgeois-worker brotherhood. Why shouldn’t they—prefect sniffing. They’ve no fortunes to compromise. Leading up to Commune. Exposed off-handedly. In long narrow alcove. A few objects including plate for printing “L’Internationale.” Plus painting of a pair of nice fat Paris rats. Communards eating during siege. In front of which straggling group of socialist ladies from Provence. Clucking embarrassed.

A jilted lover calls to say, the revolution has been domesticated. Exhibition value appreciates. I shut the book. Tisn’t so easy to capture the dialectical image, apparently, something between the surreal and the smell of a long-forgotten cookie that shoots you into your childhood. Re. backdrops, Scott has written, Like the daily news, much contemporary fiction fails to say what must be said. B agrees, Spleen is the feeling that corresponds to catastrophe in permanence. The phone is ringing. It’s Gail.

2

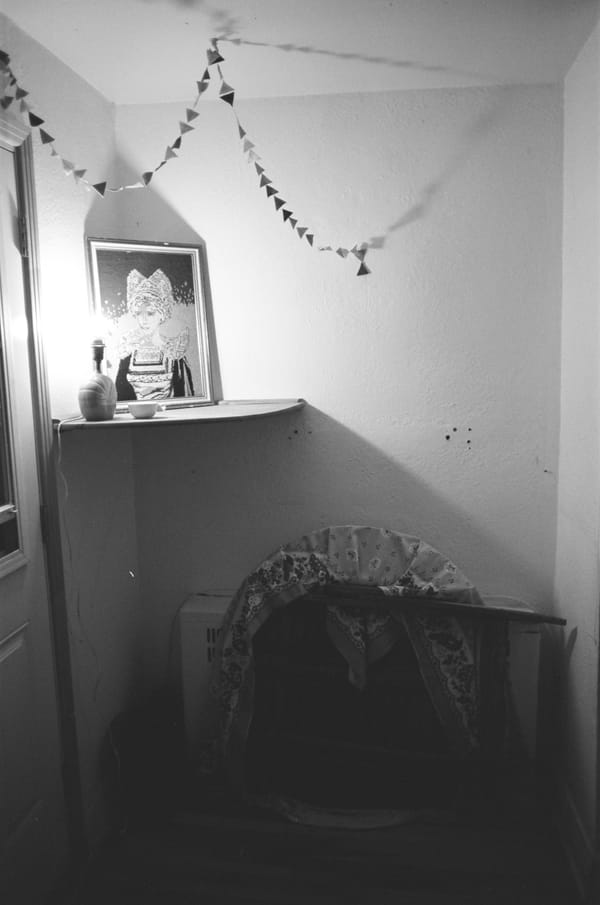

At Lana Café in Montreal, a man opens a door for another man, who looks annoyed. I sit by a window, not flaneusing today. Rêveries de la Plaza St-Hubert by Nicolas Lévesque in my bag, beside My Paris. “Immeuble à vendre” across the street. $3,500,000. Bijouterie le Roy. Inside the café is a fridge and a hum from it humming. A tuna sandwich on my plate. Salt from olives in the bread. African masks on the wall—c’est juste la decoration, says the barista. Screen on the wall: the politician expresses a “desire for change.” The passers-by squeeze past my window. Silhouettes in drag. The other side of the street is closed. Mannequins half dissembled in the window. One with no legs and one arm. One gets used to the nightmare of l’homme tronc, writes Lévesque. Like Lévesque, I have time to kill: je me trouve devant un vide de deux heures. On the screen, the politician says, “Yes we can.” This is a structure of feeling. We are told by the sign they put at the entrance to the Plaza as a harbinger of renovations that the Plaza belongs to a singular person, that this person can own it and it is self-actualizing: Ma Plaza se transforme. This is also a structure of feeling, a mode of governance, even. Scholem, B’s friend, scholar and Zionist advocate described the rumblings of Marxism in B’s book One-Way Street as “distant thunder.” How many of us have felt this far-off storm brewing in ourselves. B said he hated Marxist dogma, “but the attitude is obligatory.” You’ve changed, says the jilted lover. Ownership without responsibility: it’s a structure of feeling. A worker talks with the cook outside. They lean on metal by the cones, at the edge of the obstacle course that the Plaza has become, gang planks over deep crevasses, small steep bridges, thick gravel and labyrinthine fence-work next to saws. Droves of men in the pit with orange vests, mostly nothing-doing. The surface worker, the listless guard-type, the Mother Cone, waves and the cook laughs, her curly hair wobbling in its net. Her face looks familiar… Je viens de Paris, she says. The man who normally sits beside the metro entrance ambles towards them and asks them for change. They dig in their pockets. A stroller hesitates at the edge of the Plaza, where people squeeze out its funnel. Looks of dread all around. Look of dread on the baby’s face. I remember when the marquise came down, before they installed the new one, the pigeons, for days, would fly at the bricks, looking for their obliterated homes.

[finish reading at longcon magazine...]